JAMES DEAN: An American Icon in Novels

by Brooks Peters

by Brooks Peters

Driving home from my September sojourn in Maine, I stopped in at one of the many book barns on the roadside along the coast. I used to make my living by scouring such places for rare first editions, esoteric ephemera and the odd volume. But since closing the shop, as well as my internet business a year ago, I've been less inclined to spend time in places that bring back a swarm of memories. But on this journey, I had time to spare and entered the barn's portals without a clue as to what I might find inside. Floor after floor, I searched the shelves and came up with nothing. I was almost grateful as I slipped out the front door and left empty-handed.

But wait! What's that? I asked myself, spying a tome with an intriguing title: Farewell, My Slightly Tarnished Hero. The book was tucked in the corner of a shelf in the outside bin. If it had been any cheaper, it would have been free. I glanced at its dust jacket, on which a face peered out that looked remarkably like James Dean. Picking it up and reading the blurb on the flap, I soon realized that this novel was a fictionalized account of the famous dead icon's life:

"When film star Johnny Lewis died in a highway crash in the early fifties he was only 24. Although only two of the three movies he made had been released, his death shocked the world. If Humphrey Bogart and John Garfield would always recall the world of the 1940s, it was Johnny Lewis more than any other star who became the rebel hero of the 1950s."

I flipped the owner the coin it cost to buy it, and took it home with me.

Very few actors can lay claim to the distinction of having a novel written based on their lives. But icons are different. In James Dean's case, there have been several books. It is an odd phenomenon. One would think that a biography would be sufficient, but for some reason, authors look upon James Dean as a kind of tabula rasa on which they can dissect the tenor of the times he lived in, or even bring him back to life. Perhaps it is because he died so young. And so tragically, although the word tragic applied to someone whose car crashed into an oncoming vehicle seems a bit of a stretch. Tragedy implies a heroic struggle. Ill-fated might be a better way of putting it. It was almost a death wish on his part. No doubt that is part of the appeal. To understand why on earth this talented young man with his whole future ahead of him, the world at his feet, could die so young.

The myth-making began almost the moment he expired in that fiery crash. He hadn't died at all, some claimed. He merely pretended to die in order to escape his unwanted fame. He was that kind of guy, nervous and awkward and painfully shy. He loathed the Hollywood machine. He wanted out. I never bought those fantasies. But I did want to know what made him tick.

There was a side to James Dean that called to me, even as a young teen struggling with my own identity and sexual issues. I don't know how old I was when I first saw Rebel Without a Cause. But I suspect I was fourteen or so. I watched it alone upstairs in my father's room where the color TV was. Dad was probably away on one of his business trips. I often spent hours each day parked in front of the tube, inches from the screen. It was not uncommon for me to watch TV from 4:30 in the afternoon when I got home from school, until midnight each day. I had a little routine that amused me. I'd sit with my head perched on my right hand, the forearm at a 45 degree angle. I refused to move until my arm became completely numb. My hand would feel like it was dead. It would cease to exist. I could pinch it, jab it with a pen, slam it on a table. Nothing. No feeling whatsoever. Then I'd get up, shake it until the blood flowed back into it, and start the process all over again.

On one of these lonely nights, I just happened to turn on the TV and landed on an old movie. A bright flash of red caught my eye. It was James Dean's jacket. I didn't know who he was. I'd never heard of him. And at that moment, I had no quick way of finding out. I just watched the film unfold. I guess I'd been lucky and caught it early on. Dean was running around a sunny campus, then went on a school trip to a planetarium (although even at my young age, I thought he looked too old and pretty ridiculous as a high school student). But I didn't care about casting mistakes. I was entranced by his "look." The jeans, the pompadour, the angst in his face. And that gorgeous red jacket, which flashed across the screen like a matador's red cape in the bull ring. I lunged into the story, trying to figure out what this film was about. Who were these odd characters? The father wearing an apron? The tough kids who called each other "chicken"?

It was unlike any Hollywood film I'd ever seen. The love interest was all wrong. He wasn't after the girl. She was after him. And that friend, the school nerd who kept following him around. That was really peculiar. His name was Plato, which I found fascinating, because even at fourteen I knew that Plato was a Greek philosopher and that he was supposed to be homosexual. He had written the Symposium, which advocated both straight and gay love. I knew about such things because they were important to me. They were the only glimmers of that life available to me, tiny shards of a distant past that seemed more real to me than the phony present. I saw in this kid, the nerd named Plato, myself. And I knew that his bizarre obsession with this outcast, the James Dean character, the "Rebel without a Cause," was sexual in nature. He lusted after Dean. And stalked him. And wanted to make love to him. And did so with his eyes, if not his swollen lips.

But what really floored me was that James Dean didn't seem to mind. He didn't do what was expected, hauling off and belting the poor kid, or getting others to laugh with him. He was tender and kind and loving, and even though he got the girl in the end, it was as if he had loved them both equally. I didn't see their menage a trois as a metaphor for the family, as some critics have suggested. I didn't need to extrapolate from what was on the screen. It was there in living color. When the film was over, and Plato was dead (draped in Dean's coat, I seem to recall), I lay in my Dad's room in a state of ecstasy and devastation. Watching this picture had been like living through a strange, erotic dream.

Later, I figured out the name of the motion picture from the day's paper. And then researched the film. Like countless other Americans exposed to this movie over the years since its release, I became obsessed with both Sal Mineo and James Dean. Natalie Wood had seemed like a sister to me, from her star turns in Gypsy and West Side Story. I didn't need to fixate on her. But I saw in Mineo and Dean dual sides of my own nature and I felt that by figuring them out, I might solve the riddle of myself.

Part of the incredible aura of James Dean is the fact that he died in a horrible car accident before the film Rebel Without a Cause was released. Coming across this slice of information, after having just watched this film in a state of heightened awareness of its unique power, was too much. It was like learning the story of Christmas only to find out that Jesus's life ends in a gruesome crucifixion. What are we celebrating? The same with Oscar Wilde. I read his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray in junior high school. Then learning about his tragic life, I found out that he was persecuted, spat at, had his plays removed from the stage and died nearly forgotten after serving hard labor in prison. A similar unhappy fate befell Sal Mineo. He was stabbed to death by a pizza delivery boy turned petty thief in Los Angeles under mysterious circumstances. (Sal with Don Johnson, below, in Fortune and Men's Eyes.)

Such are our icons. They are martyrs, symbols of revelation and inspiration, but also the grim truth of life and death. And man's inhumanity to man, his endless battle with his own demons. James Dean seemed to fit into that mold. We project our innermost turmoils into his tortured soul, or what was left of it. This effect is chillingly realized in the famous erotically-charged photograph from Giant in which Elizabeth Taylor kneels like the Virgin Mary in front of Dean, posed Christ-like with a rifle for a crucifix (below).

The two other films that Dean did never had the same kind of power over me, although I certainly was moved by his performances in them. Watching them, it made no difference to me whether one had been written by John Steinbeck, and the other by Edna Ferber. Their stories were irrelevant. I was only interested in James Dean's screen time. And he did not disappoint. He tore up the screen. Later, as I grew older and wiser (as in jaded and over-educated by film teachers and historians), I saw how he was miscast in Giant. And how over-the-top his performance in East of Eden really is. Method acting is a ruse, an excuse to spill one's guts out on celluloid in a bath of tears and maudlin sentimentality. But it works, the same way that Mahler works, wrenching your heart out.

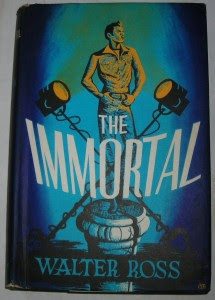

So it should not come as a surprise that authors have attempted to bring James Dean to life on the printed page. The first attempt that I know of was a book, above, by Walter Ross, a former PR rep at BMI, called The Immortal. It came out in 1958, three years after Dean's death, sporting a cover by a young Andy Warhol (whose pre-pop career began with book jackets and store illustrations.) The novel is a riot to read today. It's pulpy and pop, and cheesy. But it's as satisfying as a double cheeseburger with ketchup-drenched fries. Johnny Preston bears a startling resemblance to Jimmy Dean. The copy on the dj sums it up:

"As an actor Johnny Preston was a combination of James Dean, Marlon Brando and the Devil. As a human being, he was a mixture of child, man -- and time bomb. Other actors envied him. Producers hated him. Teen-agers copied him. Audiences idolized him. Women loved him. And so did a certain kind of man. Johnny didn't care. He'd try anything. Fast cars... books... bongo drums... marijuana... people. For him, an experience was neither good nor bad, but something to be bitten into like bread, tasted like wine and spat out like garbage."

The story is told through a series of contrived interviews, with the people who knew him best: a young starlet he was in love with; a psychoanalyst whose male patient, an actor named Hairston Sklar, was his keeper; his agent; a studio detective. Each presents his own take on the "movie star in dungarees."

The character based on Dean is a scoundrel, a social vampire, who uses sex as a means of absorbing the souls of the people around him. He is a giant sponge, sucking others dry. Early on one of his conquests finds him holed up in a bar. "I've been trying to reach you," she says to him. "I haven't been home much," he answers. I've been hiding out from the fag patrol." I suppose this type of banter was racy and daring when The Immortal was printed. To even talk about bisexuality was risqué, and risky. But since Ross was writing about an icon, a "mutant king," he got away with it. Its pre-Stonewall take on homosexuality is fascinating from a sociological standpoint. The actor Hairston Sklar seduces Preston and indoctrinates him into a "secret society" of inverts:

"A group of like-minded men who share a common attitude toward life quite far above the usual bourgeois conception of existence. Some of us are actors, some playwrights, some painters... some designers, some are in TV. We're a group that is, well, more sensitive than the herd, and so we stick together. We help one another. If you are one of us, we will help you."

Young Preston, who is only looking out for number one, sees a chance and seizes it. He moves in with Sklar, then dumps him when a richer sugar daddy comes along (a yacht-sailing queen who takes Preston to Capri.) It's rather ludicrous in hindsight, but it had a strong impact in the 50s, and was a bestseller. The book went on to become a cult classic.

There's a famous photograph of David Bowie, shot by Terry O'Neill, with a copy of the book on the floor beside him, above. The connection is made. Bowie and Dean. Immortal gods. Bowie's copy is the 1959 British edition from Shakespeare Head with a different cover illustration. (My own copy, below.)

But David Bowie, for all of his wanton past with drugs and sex, was never a tortured soul who longed for death. If anything, he seemed to be a reaction against that cliché, constantly playing the chameleon, ever evolving, never letting life or his fame overwhelm him. (Dean, below, on set of Giant, courtesy Life.)

The Edwin Corley book, Farewell, My Slightly Tarnished Hero, published in 1971 by Dodd, Mead, is surprisingly similar to the Ross novel. And I would be amazed if he did not know about The Immortal when he wrote it. Corley was a former publicist in the film business. As far as 70s novels go, which were known for pushing the envelope of good taste, this one is pretty wild, even a bit haywire. The novel is set in the present (1971) when Corley is asked by his producers to write a screenplay based on the life of Johnny Lewis, a character so similar to James Dean that it makes you scratch your head why the author bothered to change the name. You can't libel the dead.

While he is struggling to write the screenplay, Corley, who uses his own name in the book, decides to use the material he's dug up to pen a novel. (Why then begin with the conceit he is writing a screenplay? It makes little sense and adds nothing to the story.) Then in a weird bit of sleight of hand, Corley goes back in time to interview Johnny. He is part ghost, part time traveler. (Since Corley knew James Dean in real life, I find it odd that he'd use this tired Sci-Fi device to tell his story.) In one scene, he meets the Dean-inspired character in a beer joint on the West Side. Johnny takes out a knife and rubs it against the skin of the author's hand, then he twists the blade, cuts the skin, drawing blood. Since this is all happening in a bizarre ersatz flashback, it's hard to get swept up in it.

Later the book changes tone and tense, and the second half is written in the first person from Johnny Lewis's point of view. Here it becomes far more interesting and persuasive. After achieving fame in a film eerily similar to East of Eden, called Paradise Gate, the James Dean clone has numerous affairs with women, including a photographer for Life magazine; a co-star (similar to Natalie Wood) and one character vaguely reminiscent of Pier Angeli. The sex scenes are vivid and lurid. Case in point, a grim but potent bit of foreplay in the shower:

"A savage longing swept through me, and as we uncoupled, I caught her head in both dripping hands and, wordlessly, pushed her down to her knees. She looked at what I was offering with an empty expression, turned her eyes up toward me in despair, then leaned forward woodenly and began to do what I wanted. I remember calling out obscenities as the orgasm came and pulling her face against me until it was all over and she collapsed against the tiled wall, retching."

But Corley also wants to drive home the icon's downward spiral. In one bizarre scene, Johnny is watching two chicks have sex with each other. One of their companions, an aging actor named Richard Devine, wearing a dress, wig and makeup, approaches Johnny while he's staring at the girls, and seduces him.

"And, as I sank back onto a pillow and inched my way out of my khaki pants, Devine pulled off the blonde wig and I saw that he was completely shaven bald, and now his face had become very old under the garish makeup and behind the red lipstick. 'I'll do you,' he said, stroking my trembling legs, 'and then you do me.'

'Yes... yes,' I said thickly, 'I'll do you...'"

'Yes... yes,' I said thickly, 'I'll do you...'"

The way Corley writes it, one is shocked by the ugliness of it, but also disappointed by the lack of detail (especially since we've been subjected to several very graphic hetero sex scenes). The implication is that this unpleasant episode, which reminded me a bit of Death in Venice, the pansy as the grim reaper with a vile smile, has touched off a long dormant spark inside Johnny which causes him to self-destruct in a miasma of self-loathing. In the next chapter, his ex-girlfriend, who was involved in the lesbian lovemaking, now calls him a "fag." Another calls him a "miserable, sickening queer." Soon he's seen picking up boys outside a high school. The leap from a minor male seduction to such wanton depravity is not only loony but laughable. It's a sick 70s moral lesson.

After that it is only a few pages before Johnny tears off on his motorcycle (rather than a sports car, as in real life) and drives off into immortality. The vague insinuation is that he died because he was ashamed of or too frightened by his dark, homosexual urges. Considering that The Immortal had already tread this tenuous territory, it's odd that Corley could not see beyond it. Corley went on to have greater success in both fiction and film. He wrote the thrillers Grizzly and Air Force One, which were made into hit movies. Corley, below, died at 50 in 1981.

A quick Google search led me to a new book that is also a fictionalization of the life of James Dean. The Rebel by Jack Dann. Originally to be called Second Chance, The Rebel is a conjecture type of novel. What if James Dean had not had a fatal accident on that road in California? What if he had survived the crash? It's an interesting premise (similar to those novels asking what if the Nazis hadn't lost the Second World War). Dann brings Marilyn Monroe into it as well, spouting some very salty dialogue. I guess two dead icons are better than one.

What ultimately is gained by reading these less-than-stellar novels about a famous film icon? For me the allure is in the context. Especially the Ross and Corley books, which expose more about the temperament and sensibility of their time than they shed light on any mysteries revolving around James Dean. The Ross book shines a light on the Beat generation and its fascination with bisexuality that was intrinsic to the appeal of figures such as Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, and would later evolve into the androgynous idolatry so omnipresent in punk and glam rock. No wonder David Bowie was posed reading The Immortal. The connection with the cult of celebrity is apt, since he is an artist who has mined this terrain so masterfully.

Likewise the Corley book is a classic of its time, coming on the heels of the early gay lib movement and the free-wheeling, drug crazy, disco 70s. The James Dean in his book is a rebel of the sexual revolution, seeking release from pent-up erotic hangups rather than rage against society or weak fathers who sport aprons (as in Rebel Without a Cause). In the Corley book, the men in drag are the seducers, the devils, not symbols of weak parenthood, or the decline of masculinity.

But in The Rebel, Dean is given another chance. He's the Fitzgeraldian hero finding that elusive second act. He is the American hero reborn. What better metaphor for the 21st century male? We're trying to get it right this time. That's the key to James Dean and his immortality. He is an icon who is constantly evolving, reflecting back our ever changing desires -- a malleable fashion plate who suits our mercurial dreams.