The brownstone in which Dot King died is of more than passing interest. In his memoirs, the great financier, Bernard Baruch, born in 1870, told of moving in 1881 with his family from South Carolina to 144 West 57th Street, where they holed up in a tiny attic room and were taken care of by an elderly landlady named Mrs. Jacobs.

Destined to become an immensely rich stock market speculator (an interesting career, considering the later denizens of 144 West 57th Street), Baruch may have been exaggerating his early poverty, and his living quarters. For the 1880 census clearly shows that this particular address was not a boarding house at all, but a private residence owned by H. L. Horton, a now-forgotten, but at the time, leading broker on Wall Street, who had extensive dealings with J. P. Morgan (the partner so closely-tied to E. T. Stotesbury.) It's possible that late in life Baruch got the address wrong (there was a boarding house a few doors further East), or maybe he simply didn't realize that he and his family were guests of the Hortons (Baruch's father had been a noted surgeon in the Civil War and not quite as poor as Baruch liked to paint him.)

Harry Lawrence Horton, the owner of 144 West 57th Street back then, was a typical Horatio Alger figure of the Gilded Age. Born in 1832, in Sheshequin, Pennsylvania, Horton started out as a clerk in a general store, then traveled out West to seek his fortune. He ended up a grain dealer in Milwaukee. His first wife, Nellie Breen, had died there in 1864, leaving two sons, Oliver and Eugene, both of whom later died at an early age, one vanishing at sea. Horton picked himself up, started over, and moved to New York in 1865 where he set up a brokerage house on Wall Street. He took as his second wife, a New Yorker, Sarah Patten, and had two daughters with her: Blanche (1879) and Grace (1881).

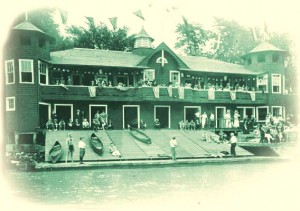

Horton first settled on Staten Island, in New Brighton, but relocated to 144 West 57th Street sometime in the 1870s. Horton later expanded the property by buying the house next door at 146, which had belonged to Thomas Tileston, another well-known broker. He combined the two structures, reconfigured the insides, added a lavish ballroom, and entertained often with his socially-inclined wife. They had at least five servants to run the house. Horton also bought the two lots behind his houses (139 and 141 West 56th Street), facing south. These included a carriage house and a hostelry. The lot was connected to the house on 57th Street by a long, narrow wooden shack. (The photo, below, shows the house at 139, the four-story at the center.) Ironically many years later I actually worked directly across the street from these buildings at 156 W. 56th Street, but paid no attention to them at the time.

Horton's daughter Blanche would marry one of her father's business acquaintances, a rising star from San Francisco by the name of E. F. Hutton. His office at 61 Broadway was right next to Horton's at 60. Hutton had not yet made his fortune, and no doubt, a marriage to Horton's daughter was a step-up the ladder for the ambitious businessman. The young couple wed in 1906 and lived at 144-146 West 57th Street, until old man Horton's death in 1915 (Sarah had died in 1899 in London). The Huttons had one child, a son, Halcourt. (As an interesting side note, Harry Horton was sued in 1905 by a woman named Elizabeth P. Berg, many years his junior, for breach of promise. She claimed he had told her he would marry her, but he reneged. The case was settled out of court.)

According to the terms of his will, Horton left the property to Blanche, while her sister Grace inherited $100,000. Grace had been wed quite young to Ernest M. Lockwood. But by the time of Dot's death, she was divorced from him, and had married Edwin F. Raynor, an automobile executive from a prominent New York family. It was probably through Edwin's influence that Grace Raynor bought a Simplex in 1914, one of the more fashionable cars of the day, popular among Vanderbilts and Morgans.

In 1917, Blanche and E. F. Hutton, above, decided to sell the property at 144-146. An announcement was made in the New York Times that the noted art gallery owner, Mitchell Kennerley, was going to buy it and move his enterprises there. (57th Street, by then, had become a fashionable center for art galleries and studios. The Art Society was just up the block.) But for some reason that deal fell through. Perhaps Kennerley had difficulty raising capital, or perhaps there was trouble with the deed. The Huttons also rented space to a furrier named Morris Schatz and later to Robert B. Mussman, who had a gallery of "paintings, etchings and mezzotints."

The same year that the Kennerley deal fell through, Hilma Louise Dunlap, a Swedish immigrant, rented the space on the ground floor of 146 and relocated her restaurant, the Yellow Aster Tea Room, which had originally been at 35th Street and Fifth, to 57th Street. Tea houses were all the rage in the Teens and '20s, and the Yellow Aster was one of the more popular. It's hard to tell from period photographs of the building's facade, which are murky and grainy, but it looks to me as if the restaurant occupied the ground floor of both buildings, and was entered by the door at 144 where the lobby was. Hilma Dunlap at some point also became the superintendent of 144-146 West 57th Street.

Blanche Hutton (bust, above) died very suddenly at the tail end of the flu epidemic in 1919 and E. F. Hutton inherited the property outright. How this must have sat with her younger sister, Grace, the Horton family's sole survivor, who'd grown up there, is open to speculation. The only clue I could find was a notice of a lawsuit between the Raynors and E. H. Hutton (his real estate holdings were called Nottuh; Hutton backwards) but I was unable to read the actual terms. I suspect they settled out of court.

Grace Horton Raynor, above, moved into 139 West 56th Street, the former carriage house behind her childhood home, and lived there throughout the 20s, devoting herself to sculpting, an art form she turned to, she explained in an interview, as a way to surmount her grief over the loss of Blanche. Her work soon gained recognition, and she received several key commissions. The building at 139, refitted with "housekeeping studios," became the hub of what appears to have been a madcap, bohemian artist community, including the well-known rhythm-dance instructor Ruth Doing, dancer Doris Canfield, opera singer Gail Gardner, photographer Delight Weston, as well as arts enthusiast Louise Bybee, all of whom lived there together and never married. (The Dance, below, by Delight Weston.)

E. F. Hutton didn't waste much time after Blanche's death to extend his rise to the top. He married cereal heiress Marjorie Meriweather Post, the recently divorced Mrs. Close (who had inherited roughly $20 million when her father, C. W. Post, died the year before). He moved to the East Side with her and bought an estate on Long Island's East End, where his son Halcourt died in 1920 after a fall during a horse-riding accident. (Death trailed E. F. Hutton a lot in those early years. But he and Marjorie, below, had a child themselves, the future actress, Dina Merrill.)

In 1920 Hutton sold the Horton property to the real estate developer Robert E. Simon, who had snatched up many of the other houses along that stretch of 57th Street under the name SIDEM Corp. He bought 150 West 57th Street in 1919, as well as rights to 148 (then owned by the Horace E. Garth family) and its back lots on 56th Street. Simon added the jewel in the crown, Carnegie Hall, to his holdings a year later, purchasing it from Carnegie's executors. According to a tribute to Simon I read, there were outcries at the time from those who feared he planned to demolish Carnegie Hall, a theme that would resurface in the 1980s when Isaac Stern once again "saved" it.

But Simon had bigger plans for his 57th Street lots, including the music hall, envisioning a skyscraper that would dominate the street, and house automobile showrooms, offices and apartments. (He also bought the stylish but somewhat faded Rembrandt next door to Carnegie Hall, one of the city's first apartment houses. It is now the site of Carnegie Tower. Next door, at 150 West 57th Street, then the Pupke residence, Fiat had its Manhattan office. One of the fashionable Strebeigh Twins, daughters of Mrs. Jerome Bonaparte, apparently ran it. That building would later become the famed Russian Tea Room, which is the only one of these brownstones still standing today.)

Back in the '20s, there had been feverish talk about building a massive bridge across the Hudson, above, at the end of 57th Street to Union City, New Jersey. Savvy developers like Simon (who was backed by his wife's millionaire brother, Henry Morgenthau) scooped up as much of the boulevard as possible in hopes of a coming land boom. A turf war ensued. The bridge never materialized, however, and the market turned south. Simon abandoned his plans to erect a tall tower there. In 1929, 144-146 West 57th Street was turned into the Little Carnegie Theater, a fine-art movie house. It stood there until the 80s when Harry Macklowe tore them down and erected his notorious "Knife Building," the sharp-edged black glass tower there. Today a Starbucks stands on the exact same spot where the Yellow Aster Tea Room once was. (142 to 150 West 57th Street, below: The Little Carnegie, at left; Russian Tea Room.)

I mention all of this real estate background because I've a hunch the building and its location played a role in what happened to Dot King. In all the news reports about Dot King's slaying, the other people in Dot's building are never mentioned by name, except Hilda Ferguson, her former roommate; and the chance mention of the Grahams by the elevator operator. That strikes me as revealing, especially considering that the police theorized that the killer had to be someone that Dot King knew and trusted, since there were no signs of a break-in. The door was locked when the maid arrived on the 15th. Only two people had a key, the maid Billy Bradford informed the police: she and her mistress, Dot. But was that true? Another report I read said that Dot kept a set of keys in the elevator, enabling her visitors to come and go as they liked. The elevator man, John Thomas, was in charge of them, receiving tips each time someone used them. If that were true, then anyone could have nicked them and gotten into her flat unannounced. But it seems unlikely that Dot would do that, especially since she was complaining to her mother, and the lawyer who drafted her will, and anyone who would listen, from her maid to her masseuse, that she was scared for her life.

What could have caused her to be so afraid? Just a few days before she died, Dot had been accosted on the street, witnesses said, by a woman who grabbed her by the hair, threw her to the ground and started pelting her, screaming at her. This was written up in the papers after her death, but no one knew who this assailant was. One paper speculated it was Mitchell's wife, Frances, Stotesbury's daughter, but that is impossible since she was in Palm Beach at the time, and by all accounts was a mild-mannered lady who had no idea her husband was having an affair with Dot King. I'm surprised people didn't speculate that it was Hilda Ferguson, her roommate. Hilda always said she moved out of Dot's flat because she couldn't stand her late night lifestyle. But that's ridiculous since Hilda was known for her own very fast-and-loose lifestyle. Perhaps she and Dot had had a knock-down, drag-out cat-fight which led to her either leaving in a huff, or more likely, being thrown out. That could explain the attack on the street (Hilda, below, had moved back to the Great Northern Hotel, just down the block.)

And on Tuesday, March 13th, shortly before her death, Dot had been allegedly beat up by Guimares himself, probably because she had just returned from a week in Atlantic City without him. Or did she have reason to be angry with him? An article I found from a few months later, tells of a bobbed-haired bandit, claiming to be Mrs. Albert Guimares, who was arrested for shoplifting from a tailor. She was wearing a fur coat identical to the one apparently stolen from Dot King's apartment. I began to wonder if Guimares hadn't been cheating on Dot around the time she was killed. And perhaps that was the woman Dot was fighting with. It would explain the marks on Guimares's hands, if he and Dot had fought. And it might also explain who the mystery woman was who phoned in later about the "pink toes" letter. She would have had reason to deflect attention away from Guimares and onto Dot's sugar daddy, Mitchell.

If one removes Guimares and Mitchell as suspects, the field opens up to include not just Hilda Ferguson and this mysterious Mrs. Albert Guimares, but also the residents in Dot's building. It would have been easy for someone living there to knock on Dot's door after 2AM, or early that morning, gain entrance and then poison her. (The swirl of cotton found on the umbrella by the door would seem to indicate that they grabbed Dot as she opened the door, then led her back to the bed where they finished her off, wittingly or unwittingly.)

And if they didn't come through the door, they might have been able to enter through a dumbwaiter that stretched from the top floor of the building to the lobby. In fact, one of the neighbors in the apartment below Dot's had told police that she had heard the sound of scuffling feet in the apartment above, and smelled a horrible odor in the dumbwaiter (chloroform has a very potent, sickeningly sweet smell.) It's possible this neighbor was Mrs. Graham, mentioned in the police report, along with her husband, as being the last people to use the elevator that night. She lived on the fourth floor. But extrapolating from census reports in 1920, it seems there were two apartments per floor. While researching the building, I came across notices placed in the New York Times by Hilma L. Dunlap, advertising rooms for rent there. An apartment on the fifth floor, which could have been the same one Dot had lived in, or the one adjacent to Dot's, facing front, included a roof garden! So it must, therefore, have had access to the roof. It's not inconceivable to imagine the killer entering from above, by swinging down into Dot's window in back.

Who were these other residents? At first, my focus remained fixated on Hilma L. Dunlap, the superintendent, who owned the Yellow Aster Tea Room, and undoubtedly had a skeleton key to all the apartments. But she's not listed in the 1920 census as a resident of 144 or 146 (the census records for the house that year are particularly confusing and poorly executed.) In fact, Dunlap does not show up anywhere in that year's census. But by sifting through real estate records, I was able to find out that Hilma Dunlap actually owned 142 West 57th Street, the townhouse next door. This came as a big surprise to me, especially since the Yellow Aster was in 144/146. And how could a single woman, who had come over from Sweden in 1883, have the capital to buy an expensive brownstone on ritzy 57th Street?

I find it particularly perplexing that Robert E. Simon would go to such great lengths to procure all the properties on that stretch of 57th Street, from Carnegie Hall east to 144 West 57th Street, but he would have let 142 slip through his fingers. Hilma Dunlap bought it a few years before Dot's death from a real estate developer named Frederic Culver. If she was working for Simon as the super of 144, the two could not be construed as rivals. It must have been an amicable relationship. But why wouldn't Culver have sold it to Simon? Was Hilma a front? But Simon would have had no reason to use a front since he'd bought the other buildings without any subterfuge. The fact that Frederic Culver was found dead later that fall, an alleged suicide, only makes the situation more intriguing.

Hilma, it turns out, was born in 1875 in Stockholm, but it's not clear when she became Mrs. Dunlap. She lived with her close friend and partner Katherine Jewett Smith for many years. Hilma and Katherine ended up moving the Yellow Aster Tea Room out of Manhattan in 1927, relocating it to Lenox Road in Pittsfield, MA where it thrived until Hilma's death in 1940 (and remained open under different owners, and names, until recently.) Kate, widow of William Smith, moved to Pasadena where she died four years later. (In her will, Hilma Dunlap left everything to her "good friend" Kate. She had no other kin and I can't help wondering if Hilma invented having been married. The 1910 Census, shows her living with "Katherine Jewett", on 58th Street; both are listed as "single." The 1930 census, in Pittsfield, shows her living with Katherine Jewett Smith, her "sister-in-law." That makes little sense since Hilma would have had to marry Katherine's brother or vice-versa. But Katherine's maiden name, I found out, was Behan, not Dunlap. One could go quietly insane trying to unravel all these loose ends.)

As for the tenants of 144, it's more difficult to get a handle on who actually lived there in 1923 when Dot was killed. The 1920 census lists a handful of people, including actress Ethel Winthrop, above, who had played Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest when it was revived on Broadway in 1910. She'd also appeared in films with the silent star Clara Kimball Young. I am certain Ethel was still there in 1923, although she shows up on 58th Street in 1930. She strikes me as the perfect candidate to be the "professional woman of the highest standing" who complained about the noise coming from Dot's flat. None of the other women living in the house were working, per the census records. And I suspect any actress who could succeed as Lady Bracknell, must have had an imperious streak. That "professional woman" had been described as having lived there for six years, so she should be included in the 1920 census, making Ethel really the only logical candidate. If she was that lady, who had ties to J. P. Morgan, then it dovetails nicely with the Hortons who also had ties to J. P. Morgan, and Mitchell, whose father-in-law Stotesbury, was J. P. Morgan's right-hand man. Researching a bit into Ethel Winthrop's life, I discovered that she was a widow, born in Canada, formerly married to James Gibbs, with whom she had a son, Harold C. Gibbs, and was friends with Fania Marinoff, Carl Van Vechten's actress wife. On the eve of Dot's death, Ethel Winthrop was appearing on Broadway in a short-lived play, The Sporting Life.

The only people I could confirm from primary records, including passport applications and voters lists, as living there in 1923, proved to be fascinating in their own right. One was an elderly lady named Fermine B. Catchings who was a Christian Scientist and a writer. Her son Benjamin Catchings, who lived with her, was a real character, one of those eccentric letter writers fond of conspiracy theories. He was arrested years earlier for making threats to Teddy Roosevelt. He makes for a good candidate for a deranged killer, but he seems to have ended his days peacefully, having settled down with a wife, avoiding future run-ins with the law.

Also in residence was a widow in her 50s named Frances Henrietta Stoddard (listed erroneously as a "male" in the 1920 census) who was originally from Vermont. Could she have had a grudge against Dot King? And what of Robert C. Sanborn, who also lived in the building? He's listed in the city directory that year as living at 144. My research uncovered that he was an executive at the Mitchell Publishing firm, which specialized in advertising products, (and, although tempting, seems to have had no tie to J. Kearsley Mitchell.) Robert Sanborn had a dark side. His wife Florence, a former vaudeville actress from Massachusetts, had once accused him of trying to kill her. She herself was a shady character, having been charged with forging her father's will in her favor. It was her own son, Robert W. Sanborn, an interior decorator, who brought the charges! Shades of the Brooke Astor saga many years later.

As I dug into the lives of Stoddard and Sanborn, I was suddenly reminded of something buried deep in my brain, a tiny fragment of information I'd filed away from one of the articles surrounding the Dot King case. When Albert Guimares was indicted for stock fraud in Boston, the police said that he had concocted a company called "King and Scott" in order to dupe people into buying securities. The "King" was for Dot King; the "Scott" was for Guimares, one of his many pseudonyms, just as he had used the name Morris and Santos at other times. But the article also mentioned that he and Dorothy kept an office at the Giske Building in New York, under the name "Stoddard and Sandborn." Searches for any information on this company yielded nothing. City directories did not have any listing for "Stoddard and Sandborn" or even "Sanborn." (The name "Sandborn" is practically non-existent and must have been a typo in the article.) Nor does the company name "Stoddard & Sanborn" show up in any news archives. Could this be Frances Stoddard and Robert Sanborn?

The similarity is too uncanny to be a mere fluke. My hunch is that Dot King and Guimares set up a fictitious company using the names of her neighbors. Why? Because she had probably convinced them to invest their savings in one of her Ponzi scams. That was the modus operandi of a pyramid scheme. She and Guimares had done it before. And there's no reason to think they wouldn't do it again. They might have even been the reason Dot moved to 144 West 57th Street. Could Robert C. Sanborn have figured out he was being duped and attacked her to get back his money? Or could he possibly have tried to recover incriminating documents that she had in her possession? It's no less far-fetched than the outlandish blackmail theories the police were bandying about. In fact, one of the news reports at the time of Dot King's death described how she was physically attacked at the Ben Hur Club on City Island the summer before by an angry investor who had been duped by her and had lost his life savings.

That was no isolated incident. She'd been arrested in Atlantic City in 1920 after a brawl in a hotel suite. A man named John Chapman had gone to her room, where she was entertaining a handsome young aviator named E. Kenneth Jaquith, and attacked her. She accused Chapman of stealing her jewelry, but had actually hid her jewels in a flower vase. She'd registered there under an assumed name. Was Chapman a jealous boyfriend, or another victim of a Ponzi scheme? Did Jaquith, below, resurface in her life? Was he the man she'd been with in Atlantic City just a few days before her death? What if Dot King had been threatened again? Wouldn't that be cause for her to fear for her life and make plans to skip town?

Let's look at that blackmail plot theory a bit more closely. Unlike the "bucket shops" criminal activity that we know for a fact Dot King and Guimares were involved in, there's no evidence that Dot King or Guimares ever threatened anyone with blackmail. It was only her brother Francis who was accused of that, and then only because he wanted a job, not a payoff. Second, it doesn't make any sense that J. Kearsley Mitchell would have feared being blackmailed over that "pink toes" epistle since he had not even signed it. And it would be hard to trace it back to him. He only came forward because he knew he had been seen at the building the night before she died and he wanted to clear his name. At that time he was the primary suspect. He needed to defuse the situation. As far as I know, he never once claimed he was being blackmailed. It was only the press that speculated along those lines, and with absolutely no evidence.

The Stoddard & Sanborn link I've uncovered does point to one other potential suspect, perhaps the best candidate for the killer I can come up with: Guimares's friend and alibi Edmund J. McBrien. When McBrien was interviewed by the police, he explained that he too worked at "Stoddard & Sandborn" with Guimares. He was described as a stockbroker (which is how he is listed in the 1930 Census, living with his brother Harry, in Manhattan). There is some confusion over his exact name. Most often his name is spelled "McBryan" in news reports. But he shows up in most census records as "Edmund J. McBrien," born 1899 in New Haven, CT. His father Christopher was a mason; his brother Christopher, Jr., ironically, was an IRS agent.

McBrien's name reappeared in the papers in 1929 when he was involved in another sensational scandal, the suspicious death of his girlfriend Aurelia A. Fischer. She was the same "mystery blonde" who had played such a prominent role in establishing Guimares's alibi in the Dot King case, swearing to police that she had spent the night with him and McBrien at the Embassy Hotel, before fleeing to New Haven, where the authorities questioned her. In October 1923, just six months after Dot King's murder, Aurelia Fischer had married a much-older stockbroker named Herbert M. Dreyfus. This strikes me as odd, since she was obviously McBrien's girlfriend earlier on. But by 1928 her marriage to Dreyfus was over; McBrien had been named a correspondent in her divorce case.

In October 1929, Aurelia, above, was visiting her family in DC. She'd been to a party at the Colonial Canoe Club where her brother William was Secretary. McBrien was with her. She'd gone out with him to take the air and stood at the edge of a promontory overlooking the Potomac. Her body was found later on the boat landing where it had fallen. Many believed McBrien had pushed her because she had threatened to expose the truth about what really happened to Dot King. He denied it. Her parents demanded a trial. A grand jury was formed.

At the inquiry, it was revealed that shortly before her death Aurelia had told her family that she feared for her life because she had perjured herself in 1923 when interviewed by the police. She claimed that she had not been with Guimares on the fateful night. The jury decided that there was insufficient evidence to press charges against McBrien and the case was deemed an accident. Since then commentators have speculated that McBrien killed her to hush her up, lest his best friend Guimares be arrested for Dot King's murder. This strikes me as implausible. Nothing would implicate Guimares more than Aurelia's sudden death. It would be the last thing Guimares would have wanted, especially since by then Guimares had served his prison term for gun possession, and had married a rich woman. I don't buy that theory. (Guimares, for the record, died at 56 years old in 1952. He died at the Madison Hotel in Manhattan, where he was registered under the name Albert Santos.)

So where does all this leave us? It leaves us with Eddie McBrien, stockbroker and partner of Dot's with the phony "Stoddard & Sandborn" company, and boyfriend of Aurelia. It seems far more likely to me that if the death of Aurelia Fischer was his doing that it would be to save himself from the gas chamber, not Guimares. Perhaps he was the one who visited Dot King that fateful morning, and had brought the chloroform (possibly from Guimares's reported stash) along because he knew she would not have willingly given him entrance to her rooms. They were business associates, not lovers. Was he there then at Guimares's bidding? I doubt that too. I think, if he was in fact the killer, that he had his own motive, most likely related to the collapsing Ponzi scheme surrounding Stoddard & Sanborn. Perhaps in the future, the entire story of what happened on the Ides of March, 1923 at 144 East 57th Street will finally come to light.