In lofty discussions of pioneering gay writers in fancy literary journals the name George Baxt rarely comes up. But Baxt, a former agent turned writer, was far more influential than he is given credit for. His work ranges from theater and film (he wrote the screenplay for the cult fright flick Circus of Horrors) to a series of popular mystery novels, including the ground-breaking pre-Stonewall classic: A Queer Kind of Death.

George Baxt was a true character, the kind of guy you'd love to have at a party, but would hate to have on your bad side. He had a wicked tongue, spitting out barbs like watermelon seeds. I never met the man. But I'd heard over the years about his enormous wealth of knowledge about the theater, old talkies and movie stars. He knew where all the bodies were buried and was never shy about spilling the dirt. Reading through his hilarious books, of which I have a small collection, I got to thinking. Why isn't George Baxt better known? It's a riddle I tried to solve the only way I know how, by reading everything I could find about him.

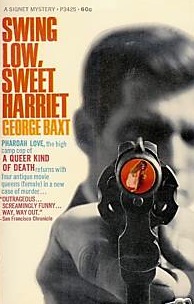

I first encountered the name George Baxt when I stumbled upon a copy of A Queer Kind of Death. Published in 1966, it featured a campy gay detective, and a black one to boot: Pharoah Love. (The spelling mistake in his first name was deliberate). Pharoah Love was an audacious "cool cat" who loved jazz, his swanky Jaguar and sexy white boys. Campy, outrageous, arch and far-fetched, the novel created a sensation. This was before gay liberation and very few "legitimate" books were published with openly homosexual heroes. (For the record, there had been gay detectives in previous works, most notably, Rodney Garland's The Heart in Exile (1953) and The Gay Detective by Lou Rand in 1960.) Baxt was shocked by the response. He hadn't thought it was that unusual. He was basically writing about people and the life he knew in Greenwich Village and the rest of Manhattan. But the book struck a Pre-Stonewall nerve. It was hip, irreverent and sexy. Anthony Boucher of the New York Times gave it a rave review, noting that the salty tale "deals with a Manhattan subculture wholly devoid of ethics or morality. Staid readers may well find it shocking, but it is beautifully plotted and written with elegance and wit." Rarely has a first book found such a devoted audience. The love affair with Pharoah Love continued. Baxt followed Queer up with two Love sequels: Swing Low, Sweet Harriet; and Topsy and Evil.

Later, I re-encountered Baxt's work when I dove into The Dorothy Parker Murder Case, the debut title in a series of mysteries he concocted in the 80s, using celebrity sleuths. He commandeered Noel Coward, George Raft, Tallulah Bankhead, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, and even Alfred Hitchcock into his series, penning riotous, madcap capers with each of them that are wickedly clever and entertaining.

For my money, none is funnier than the first one. The Dorothy Parker Murder Case is a marvel to read. The writing is fluid. Self-assured. Totally committed. And absolutely hilarious. It's as if Baxt were channeling Dorothy Parker herself which is no small accomplishment. It opens with a harrowing bit of black comedy. Dorothy Parker is attempting suicide in the john of her hotel room after ordering lunch. "After slitting her wrists, Dorothy Parker sat in the bathroom waiting patiently to be rescued." That's all he needed to say. It sets the wry, but touching tone for the entire tale. I don't think anyone has written a better celebrity sleuth mystery before or after. But Baxt had the inside scoop. He was always writing about people he knew personally. He was a familiar figure in the worlds he wrote about. The more I delved into his lively, but checkered past, the more I realized where he got the raw material for his scandalous books.

|

| Pulp Sensation: Pharoah Love |

Like his most popular character Pharoah Love, Baxt was a fabulous creature of many talents and a cat of nine lives. But he also shied away from revealing interviews. Armed with very little to go on, I set out to see if I could fit together a few shreds of his life story. His name appears on Wikipedia, and on IMDB as the screenwriter of such horror hits as the aforementioned Circus of Horrors and Horror Hotel. But there is only scant biographical information given.

|

| Cult fave: "Circus of Horrors" |

Luckily I found an obituary for him written in England. (Except for a few isolated notices, the American media failed to mention his passing in 2003.) The obit focuses primarily on his film work in that country. Baxt had moved to England in the 50s and wrote most of his scripts there. Variety had posted a rather perfunctory obituary, again primarily because of the screen credits. But there was scant material for a researcher to rely on to find out where he came from and who his family was.

His book jackets provided a few more intriguing details. On the back of A Queer Kind of Death he wrote: "George Baxt was a dropout. He left Brooklyn College to pursue a writing career." In another, he said he was born on a kitchen table in Brooklyn, New York. So taking that as a starting point, I did a little census-scouring and found that he was born in Brooklyn on June 11, 1923, the son of Samuel Baxt, an operator at a clothing manufacturer who came over from Minsk, Russia around 1906. George's mother was Lena Steinhouse whom Samuel had married in 1910. George had several siblings, a brother Morris, a sister Esther and a sister Juliette. They lived on Dumont Avenue. Nearby is an Isidore Baxt whom I presume is his uncle. He also came over from Minsk in 1906. By 1930, George's father had opened his own grocery store on Avenue L.

Baxt joked later that he had an active sex life as a boy in Brooklyn. He was not shy. One commentator quoted him as saying he "regarded gay sex among the Irish, Italians, and Jews as normal." Baxt settled down "with a boyfriend in high school, although he claimed to also have sex with teachers, particularly those in Physical Education." He was probably just being his old provocative self. But it does indicate that Baxt was a rebel with a cause early on. He claimed in yet another wry author's note that his first published piece appeared in the Brooklyn Times-Union when he was nine. He was paid a couple of dollars for it and got bit by the freelance writer's bug. He scribbled articles in high school and won the Columbia Scholastic Press Award. He sold his first radio script at 18.

Baxt went to City College and Brooklyn College before dropping out to pursue his passion for the theatre. His first venture was a musical play called Pity the Kiddies which was performed in 1942 for one night only at the Barbizon Plaza's concert hall. In March that year he performed as an actor in Theatre of the Soul by Nicolai Evreinov, staged by his friend William Boyman.

Baxt claimed to have been in the armed services which might explain the gap in his career credits from 1942 to 1945. But I have not found any records of such service. He also claimed to have been a "propagandist for Voice of America." In 1946, he wrote a one-act play Laughter of Ladies that was produced at a theatre showcase on 47th Street. A year later he penned a comedy, Alex in Wonderland, about a Jewish family in Canarsie. Boyman announced that Molly Picon, the Yiddish actress, was set to star in it, but it never seems to have gotten off the ground. Later he changed the title to Make Momma Happy and it made the rounds. At one point Sidney Lumet (son of the famous Yiddish actor Baruch Lumet, and later film director) was slated to appear in it.

|

| Laughing Lady: Grayson Hall |

In 1948 Blanche Yurka announced she was to star in Laughter of Ladies. Then Estelle Winwood was added to the cast. (In his Tallulah Bankhead book, which features Winwood, Baxt makes it clear that Yurka was fired because the producers and directors found her wanting. He also makes the outlandish claim she was a murderess, but that's another story.) The play failed to get picked up. It was eventually staged with Grayson Hall (of Dark Shadows fame) in a New Jersey summer theater in 1953, and went on tour to Hartford and Philadelphia in the fall. It never appears to have made it to Broadway.

Obviously George Baxt was having a hard time gate-crashing the Great White Way. He often got pocket change by pitching stories to Walter Winchell. "Always on the hunt for new clients," his UK obit says, "he would ride in the elevator in the Algonquin Hotel to find out who was staying there." This experience would serve him well later in his Dorothy Parker novel. As an actor's agent, he was not always a good judge of up-and-coming talent. He admitted to throwing a young James Dean out of his office because the kid needed a shower!

|

| Missed Opportunity: James Dean |

Later Baxt found side work as a disc jockey to make ends meet. An announcement in the Times in 1953 says he had signed a rental lease at 449 E. 58th Street. (Apparently there was nothing odd in those days about publishing one's address in the paper). Judging by the tony East Side address, he couldn't have been doing too poorly.

In the mid-50s he segued from radio into television. He scouted talent for The Big Show, helping Tallulah Bankhead land a lucrative gig on there. By 1955 he penned a comedy for NBC called The Way Things Happen starring Peter Lind Hayes. He made a bigger splash with a David Susskind production of Mrs. Miniver for TV, starring Maureen O'Hara in the Greer Garson role. Keir Dullea and Juliette Mills co-starred.

In 1956 he returned to the theater, writing a sketch for Ben Bagley's show The Littlest Revue at the Phoenix. But nothing came from that. His dream of making his name on the stage came to a crashing halt.

Faced with the distressing fact that he couldn't catch a break on Broadway, and that several of his clients were blacklisted as Red sympathizers, Baxt escaped to England, and accepted an offer from producer Hannah Weinstein to work on the British TV series Sword of Freedom. "I went to England on a three-month contract and stayed five years," he later said. The show starred Edmund Purdom, of The Student Prince fame, as an artist and freedom fighter in Florence during the Renaissance. "A lot of later famous people starred," Baxt quipped. "Joan Plowright played Mona Lisa. I wrote 10 of the 39 episodes. I used to call it 'The Sword of Boredom.'"

Eager for a change, Baxt began writing horror films for British producers, and struck gold. Circus of Horrors was cited by the New York Times as "the crispest, handsomest and most stylish movie shocker in a long time." The eerie 60s camp classic Horror Hotel (aka City of the Dead) from Amicus Films, featured a suave Christopher Lee in a bookend cameo as a devilish professor.

But horror was not all Baxt was up to. One of his niftiest flicks was Payroll, a taut gangster noir, featuring Beckett actress Billie Whitelaw and handsome actor Michael Craig.

But horror was not all Baxt was up to. One of his niftiest flicks was Payroll, a taut gangster noir, featuring Beckett actress Billie Whitelaw and handsome actor Michael Craig.

In 1961, Baxt wrote the eerie thriller Shadow of the Cat, about a fierce feline seeking revenge on those who murdered its mistress. Creating an aura of suspense, director John Gilling filmed it entirely from a cat's-eye view.

Other credits include Burn, Witch, Burn. Not surprisingly, Baxt also had a hand in the camp classic The Abominable Dr. Phibes starring Vincent Price. Although uncredited, Baxt is said to have come up with the now-famous device of having Phibes rise out of the floor playing his ghoulish pipe organ.

Perhaps longing for his show biz roots, or the gay life of Manhattan, Baxt returned to Amerca in the early 60s. He landed a plum assignment, writing a new adaptation of The Scarlet Pimpernel for CBS. Starring Maureen O'Hara, Zachary Scott and Michael Rennie, it was another David Susskind hit. The Times called it "exciting and richly mounted."

He collaborated on a new suspense series My Son, the Detective that was probably too camp for its own good. He also wrote episodes of The Defenders. In 1963 Broadway beckoned anew. Judy Holliday was set to play in Baxt's latest play, Not in Her Stars, with Martin Gabel. But nothing materialized. Gabel went on to act in Marnie instead. Then in 1964 the play was revived. Nancy Walker the comedian was slated to direct. Jane Wyman hoped to bring it to Broadway with co-star Anita Louise. Alas, it too, like Phibes's organ, was a mere pipe dream.

No doubt these repeated failures broke Baxt's spirit. He abandoned the stage completely. For two years he seems to have done nothing, or so reports in the Times indicate. Two years of silence. But Baxt broke that silence with his outspoken first novel, A Queer Kind of Death and his career took a whole new turn. He wrote the two Love sequels, then launched a new series of "wild, wacky, and weird" mysteries featuring detective Max Van Larsen in such farcical fare as A Parade of Cockeyed Creatures. Among Baxt's other books are The Affair at Royalties (1971) and Burning Sappho (1972).

In 1971 Baxt wrote the screenplay for a little known film called Man Bait, featuring Peter Attard and John Carson. I have not seen it, and there are no reviews of it on IMDB. One contributor in the Trivia column dubbed it "Britain's first gay sex comedy."

|

| "Horror on Snape Island" Poster |

In 1972 Baxt returned to the silver screen to write Tower of Evil (aka Horror on Snape Island), based on his novel of the same name. He did not always have the Midas Touch when it came to books. His 1979 novel, The Neon Graveyard, a scathing send-up of Hollywood, was panned by Newgate Callendar in the Crime Books review section at the Times. That proved to be one of the few bad notices he ever got. Even the great doyenne of mysteries, Ruth Rendell, who was not known for dispensing superlatives with ease, described Baxt as "brilliant and hilarious," adding, "I love reading George Baxt."

Baxt caught his breath and dreamed up the celebrity sleuth series which put him back at the top of his game. He even wrote himself into a few, depicting a character named George Baxt. It was his own Hitchcock moment. He continued to write until the 1990s. According to Village Voice theater critic Michael Feingold, who wrote about Baxt and interviewed him when the latter was living in Los Angeles, Baxt was very proud that the clever epigrams in the Parker volume were all his own creation. "He told me that the people who made Mrs Parker & The Vicious Circle," Feingold recalls, "had tried to get him to share the historical basis for the lines he wrote so they could use them in the script. He said, 'I invented them and if you want to use them, you'll have to pay me!'"

|

| Witty Muse: Dorothy Parker |

Towards the end of his career, he was wooed back into writing again about Pharoah Love, his most popular creation, whom he'd killed off in Topsy & Evil. He penned two "sequels," A Queer Kind of Love and A Queer Kind of Umbrella, set in Chinatown and using a second Pharoah Love character. But they did little to revive interest in him or his earlier work. By then his accomplishment in writing successful gay mysteries was overshadowed by the impact of Joseph Hansen and his Brandstetter mysteries which were more in the traditional hard-boiled vein and more accessible to a wider audience. Most people I've talked to who are interested in vintage gay literature have never even heard of George Baxt. He died at the age of 80 in 2003. Typically the New York Times didn't even bother to write him an obituary even though he had been one of their favorite authors.

I wish I had met George Baxt. Maybe somewhere along the line I did, but didn't know it. Although from what I've read that sounds hard to do. Journalist Tom Vallance once described meeting Baxt: "I had lunch with Baxt just once, several years ago in New York, and found him wonderful company with great zest and a rich fund of anecdotes. He could also be caustic, and he had been known over the years to have alienated some of his friends. His family described him as 'outrageous and curmudgeonly, a complaining, perpetual naysayer', but added that he always remembered to phone on birthdays and give presents to the children."

I can see George Baxt as a doting crotchety uncle. But one also gets the sense reading about him that he was pretty much a loner. On one book jacket he described himself as "a collector of film and theatre books [who] sits up till all hours for old movies on television." He said his best friend was his VCR. Clive Hirschhorn, author of The Warner Brothers Story, recalled to Tom Vallance that George Baxt's "knowledge of movies was truly vast -- he could name all the girls who dance on the aeroplane wings in Flying Down to Rio!"

While there is not much else about George Baxt online or elsewhere, he is mentioned in a fun book of recollections by Wendy Werris called An Alphabetical Life. In it she describes a luncheon at Pete's Tavern in Manhattan in 1986 when she first met him. "Baxt was a rather small man in his mid-sixties, plump yet graceful and with thinning gray hair. Although I was friends with several gay men at that time, I had never met such a flamboyant queen as he. If you can imagine a swish, fey and girlish Phil Silvers, you'll have a picture of George Baxt. He was hilarious and irreverent. He batted his eyelashes to make a point when telling a dirty joke. His Brooklyn accent was delicious, and he had stories to tell about every great star from the Golden Age of Hollywood and beyond. You never heard dirt dished until you heard it from the mouth of George Baxt."

Wendy Werris goes on to share some of his sizzling anecdotes involving Sal Mineo and what randy things Baxt wishes Gidget had done in her movies besides just going to Rome and Hawaii. In just a few snippets of conversation, Werris captures the ribald spirit of the man. It's the same priceless humor you can enjoy simply by reading any of George Baxt's campy books or seeing one of his thrilling movies.